February 8, 2022

As the United States of America continues to experience anti-Asian violence, acts of hatred are nothing new in the Asian community. Although the demographics of the perpetrators have changed, the unfairness and sometimes hopeless cycles of violence continue.

This incident happened in Davis, California, nearly 40 years ago.

On May 4, 1983, tensions between Asian students and a small group of Caucasian students reached a boiling point. What started as a verbal argument that reportedly lasted only a few minutes, escalated into the stabbing death of a 17-year-old Vietnamese student named Thong Hy Huynh.

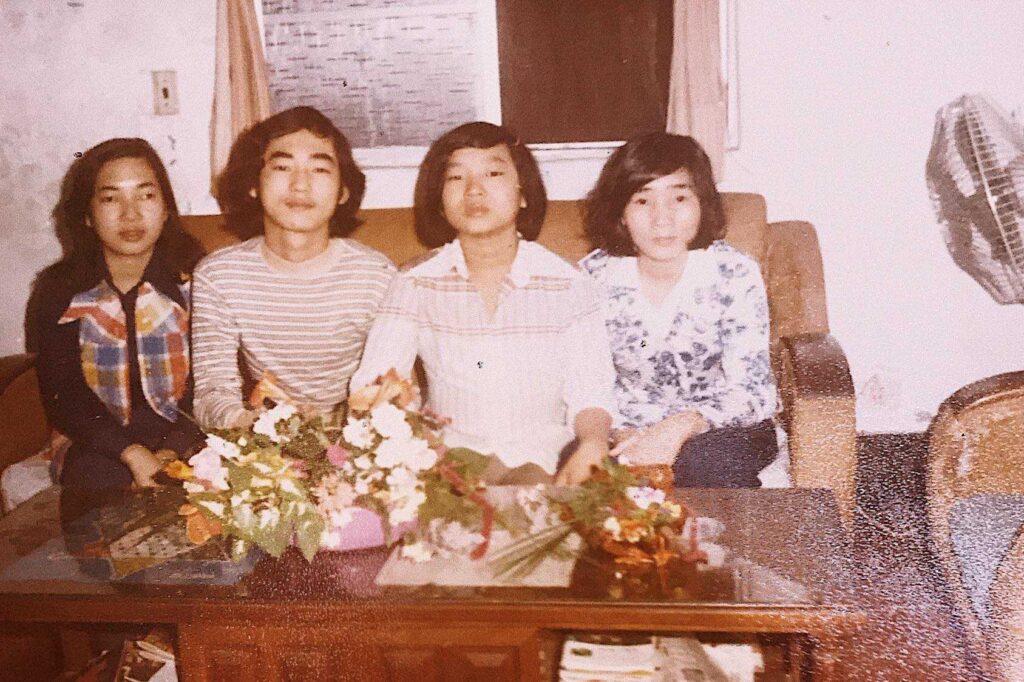

Huynh’s family, consisting of his mother, brother, and sister fled wartorn Vietnam just three years earlier.

Community activist Grace Kim was a teacher at Davis High at the time.

“I came into my classroom after lunch, and I was going to just start class,” Kim told KCRA3 NBC. “Suddenly, outside, I heard lots of noise, and screaming.”

According to Kim, Davis High only had a handful of Vietnamese students at the time.

“One of them was stabbed,” Kim remembered. “All bleeding. All the teachers came out because of the screaming.”

Police Chief Jerry Gonzalez and teachers found Huynh severely wounded on the ground outside of the science wing. Huynh died two hours later at the hospital, according to KCRA3.

Police arrested 16-year-old James “Jay” Pierman for Huynh’s murder. Pierman fatally stabbed Huynh in the torso.

“[Pierman had] just transferred to our high school,” said Kim. “I heard that he had lots of problems in Long Beach. That’s why he moved to Davis. He bothered those [Vietnamese] boys almost every day. Calling them names, and threatening them.”

What happened to Pierman?

A jury convicted Pierman of voluntary manslaughter and sentenced him to six years in juvenile prison. Needless to say, the verdict shocked Huynh’s family and supporters who all expected a harsher punishment.

“We were very disappointed with the verdict,” stated Diane Tomoda of Asians for Equal Rights in a 1984 publication of the Pacific Citizen, a paper managed by the Japanese American Citizens League. “We were expecting at least a second-degree murder conviction.”

“A verdict of voluntary manslaughter implies an accident,” Alan Yee, president of Asian Americans for Justice, said in the same publication. “Our coalition is evaluating the trial … and we’re thinking of taking it to the civil rights department, like in the Vincent Chin case.”

A year earlier (1982), Chinese-American Vincent Chin was savagely beaten to death by two Caucasian men in Michigan. The two Caucasian men, both ex-Chrysler employees blamed Chin for their unemployment because of the Japanese automobile industry. They thought Chin was Japanese.

Pierman’s mother at the time called her son’s verdict “unfair.” She claimed her son came to the rescue of his friend Russell Clark, who was involved in the argument, according to KCRA3.

“[My son is] responsible for caring … he’s responsible for being a human being,” stated Rose Mary Pierman. “Everything else after that was a total accident.”

Pierman’s defense attorney Peter Maas is quoted saying that “the incident had racial overtones but Mr. Pierman is not a racist,” further adding that Pierman had once dated a Korean woman, reports KCRA3.

“[It was] a really sad situation,” said Kim. “They didn’t speak English well, and no money.”

To add insult to injury, on the day of Huynh’s funeral, a group called the “White Student Union” littered Davis High campus with racist leaflets, which blamed immigrants for taking away jobs from “white people.” Davis High staff worked quickly to remove the offensive literature before Huynh’s body arrived.

“This is contrary to everything we believe in here,” said Eric Murphy, principal of Davis High at the time. Murphy added the White Student Union had no ties to the school. “They are outsiders. This is the first time we’ve ever been confronted by something like this.”

According to KCRA3, after Huynh’s death, the city of Davis established a Human Relation Commission to address hate incidents. The commission gives out the Thong Hy Huynh award every year to recognize local achievements in civil rights activism.

Huynh’s photo was shown in the 1983 edition of the Davis High yearbook, however, there is nothing written about his death. Pierman is not listed in the yearbook.

KCRA3 tried to reach out to Huynh’s family members for this story, which was published back in 2021. They declined to comment on camera, however, Huynh’s niece wrote a statement addressing what happened in 1983.

The statement reads in part: “My uncle was murdered nearly 4 decades ago, but the suffering my family felt surmounts time. My family’s homeland was ravaged and taken away from them, and my grandma did the best she could to protect her family. She immigrated to the United States as a single mother of three to give her children a better chance at life, and in 1983 that right was stolen from her youngest. Like many other immigrants, my family wasn’t greedy— they didn’t care to live extravagant or comfortable lives. They just wanted to survive. The crime committed against my uncle Thong Hy Huynh was one fueled by anti-Asian discrimination and this is not up for debate. To refute this is to deny the ugly existence of racism that has pervaded through centuries of systemized white supremacy; to turn a blind eye is a political statement in and of itself. My uncle is just one of many who have been failed by the American rejection of the Other. My uncle’s killer did just six years at the California Youth Academy and has never admitted responsibility for what he did. He ran off to the school parking lot, got his knife from his truck, ran back and stabbed my uncle through his rib cage. Once. That was all it took.”

The statement ends by saying: “No one is born in their homeland wanting to become a refugee; my family had to flee Viet Nam because of the militarism and destruction that America brought upon us, and that view of us as an enemy followed my uncle to death’s door.”

The entire statement can be accessed by clicking HERE

Feature Image via KCRA3 NBC